How is milk priced in the United States? An overview of FMMOs

Author

Published

9/28/2023

Note: For more information regarding how milk is priced in Iowa specifically, please visit this link.

A common joke when discussing milk pricing is that only three people in the world know how milk is priced, and two of them are dead. It is true that milk has one of the longer and more nuanced pricing systems, however, it is not impossible to understand. This article provides an overview of how milk in the United States is priced.

Most of the milk in the United States is priced under Federal Milk Marketing Orders (FMMOs). FMMOs are federal laws that specifies the minimum price producers must be paid by handlers for their milk. In FMMOs, milk processors are referred to as “handlers” of milk. This article uses the same terminology.

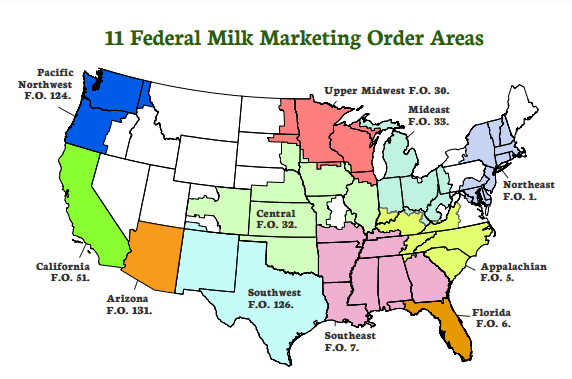

There are 11 different FMMO regions across the United States shown in Figure 1. The majority of Iowa is in the Central Order, but some northern counties are in the Upper Midwest order. As discussed later in the article, all of the milk sold in each order can be pooled and sold at a uniform price. This allows all producers in the same order to receive the same base price for their milk before adjusting for differences in milk components and quality.

Figure 1. 11 Federal Milk Marking Order Areas; Source: USDA-AMS

There are a few important things to note about FMMOs. First, an FMMO establishes minimum prices, but processors are free to seek dairies that offer certain kinds of milk and offer more for that milk if they desire. They just cannot pay below the minimum price set by the FMMO. Second, minimum prices do not apply to cooperatives, only to private handlers. Milk handled by cooperatives is still accounted for in pooling, but cooperatives can pay lower prices.

At its core, milk is priced on the principle that farmers should be paid for milk based on the value of the products that can be produced from milk, less a make allowance (processing costs). In a competitive market this principle is expected to hold true. Using this underlying principle as a guide, the formulas to calculate milk pricing were developed.

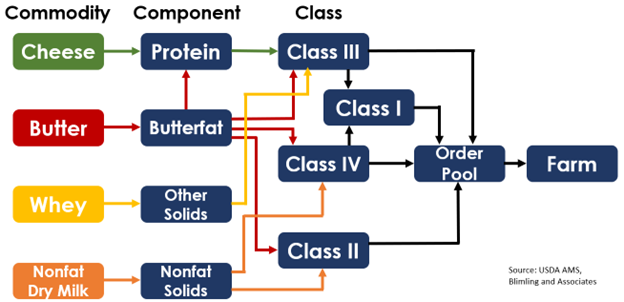

Figure 2 provides an overview of the discussion that is to come. It illustrates how price information flows through equations to get a farm price. The order pool is a natural dividing point for the discussion in how milk is priced. Everything to the left of the order pool primarily focuses on how much money handlers of milk must pay into the order pool. The formula used to calculate the money farmers are paid out of the pool is different. We first focus on prices handlers pay into the pool before concluding with a discussion of what prices producers receive from the pool.

Figure 2. “Three C’s” of Federal Milk Marketing Order Pricing; Sourced from AFBF

Handler Obligations for Milk

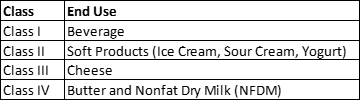

Handler contributions to the pool are based on the end use of their milk. Milk is put into one of four classes based on its end use (Table 1).

Table 1. End Use of Dairy Products by Class

Class is one of the three C’s that are often referred to in discussions of milk pricing. The other two C’s are Commodity and Component. Commodity refers to the commodity prices that are referenced to get a value of the products produced from milk. The four commodity prices currently used are: cheese, butter, whey, and non-fat dry milk (NFDM). Components values are derived from commodity values. The four component prices used are protein, other solids, non-fat solids (which is the sum of protein and other solids), and butterfat.

The relationship between the three C’s is shown in Figure 2. Commodity prices are used to determine the value of components in milk, and component values are used to determine the value of classes of milk. The USDA conducts surveys on the 4 commodity prices listed below and publishes the data in the weekly National Dairy Products Sales Report (NDPSR, slug id = 2993).

Commodity to Component to Class

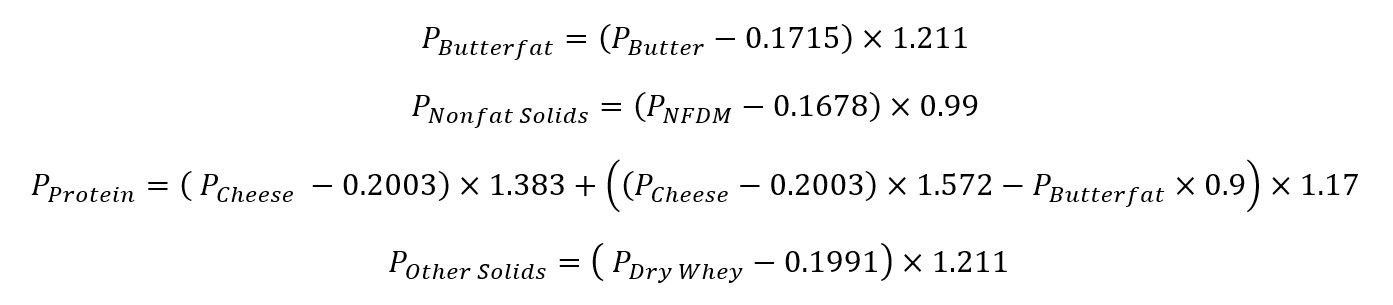

The milk pricing process starts with the USDA conducting a survey of handlers who sell wholesale commodities. From these surveys the prices of the four commodities are determined. Then, the equations below are used to calculate component prices using commodity prices. In addition to the survey data on commodity prices, fixed yields and make allowances are also included. In the equations below, P represents the price of the product:

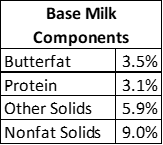

After calculating component prices, base class prices can be calculated. Base class prices use base component levels that are set at fixed levels (Table 2). Note as mentioned earlier than nonfat solids is the sum of protein and other solids.

Actual component tests of milk almost always differ from base component levels. Base component levels are used to set base milk prices for reference by those in the industry. Also, in some cases handlers are obligated to pay for milk on base component levels and not actual test component levels. These cases are discussed in more detail later.

Table 2. Base Milk Components

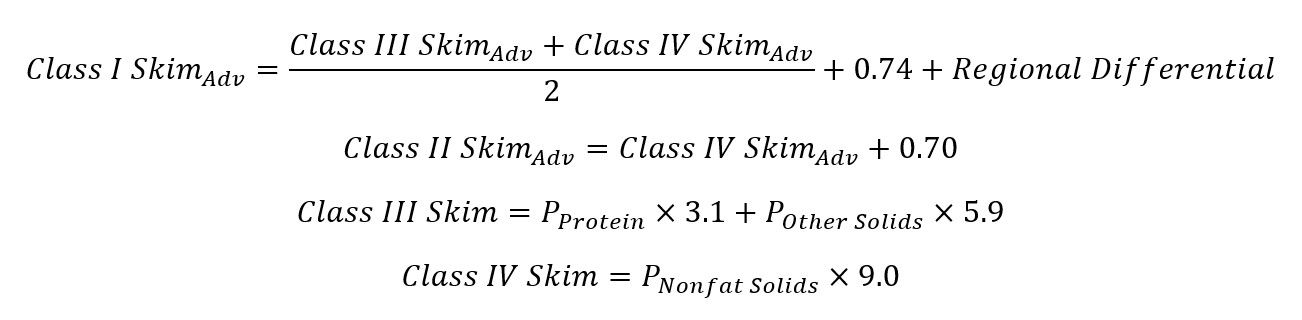

It is common to break the value of milk into skim and butterfat. First the value of skim milk is calculated, then the value of butterfat is added to get the full value of milk. Skim class prices are calculated using the equations below:

Class I skim milk is a function of Class III and Class IV milk as well as a regional differential. These differentials were originally put in place to help encourage beverage milk production in areas that are milk deficit. An outline of current reginal differentials is shown in Figure 3. These differentials are fixed constants that can only be changed by an amendment to FMMOs.

Class I skim milk is a function of Class III and Class IV milk as well as a regional differential. These differentials were originally put in place to help encourage beverage milk production in areas that are milk deficit. An outline of current reginal differentials is shown in Figure 3. These differentials are fixed constants that can only be changed by an amendment to FMMOs.

Figure 3. Class I Price Differential Ranges; Sourced from AFBF

Class II skim milk is a function of Class IV milk plus a differential that adds a premium.

Note both Class I and Class II skim prices are announced earlier than Class III and Class IV skim prices. That is why the advanced factor (adv) is noted for both prices. Class I and Class II prices are announced the by the 23rd of the preceding month they are used. Class III and Class IV prices are announced by the 5th of the following month. Because both Class I and Class II are functions of prices announced well after they are, advanced/preliminary prices are used in all equations needed to calculate these prices.

Class III skim milk price is a function of the price of protein and base protein component level as well as the price of other solids and the base other solids component level. The base Class IV skim milk price is a function of the price of nonfat solids and the base nonfat solids component level.

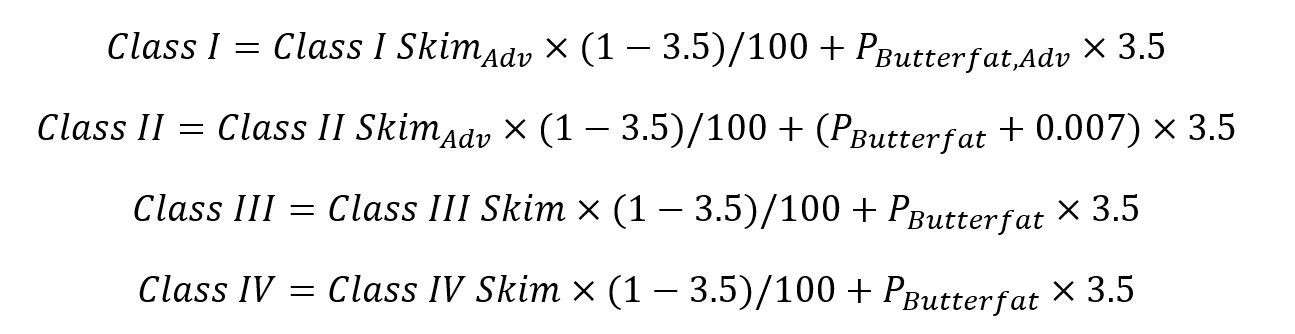

The final step in calculating the class prices of milk, and thus the handler obligations for milk, is to add the value of butterfat. This is done using the equations below:

Each equation takes the value of skim milk times the percentage of skim milk in full fat milk and adds the value of butterfat. In the above equations, 3.5 represents the base level of butterfat. Also note Class II milk gets a premium added for butterfat.

More colorful examples of the above equations are also available from the USDA at the following links. These each focus only one class of milk at a time instead of all four at once and can be useful for those not familiar with milk pricing.

Class I: https://www.ams.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/ClassIworksheetfinal.pdf

Class II: https://www.ams.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/ClassIIworksheetfinal.pdf

Class III: https://www.ams.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/ClassIIIworksheetfinal.pdf

Class IV: https://www.ams.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/ClassIVworksheetfinal.pdf

Pooling Considerations: Handler

So far, the calculation of base milk prices has been covered. These are the base prices handlers must pay into the pool for the milk they receive. However, there are a few other additional factors that must be considered on the handler side before moving to the producer side of things.

The largest is the fact that there are two different milk pricing approaches used in the US: milk component pricing (MCP) and skim-fat pricing. Each order decides which approach they will use. Of the current 11 FMMOs, only 4 use skim-fat pricing (Arizona, Florida, Appalachian, and Southeast) while the rest use MCP.

Under MCP, all handlers except Class I handlers must adjust their payments into the pool for the actual milk components they receive. They do not use base component levels in their milk pricing, again except for Class I handlers. Class I handlers must pay for actual butterfat received, but always pay for protein and other solids based on the base component level.

Skim-fat pricing is different from MCP. Under skim-fat pricing, all handlers pay for base components levels for protein and other solids but pay for actual component tests for butterfat.

Pooling Overview

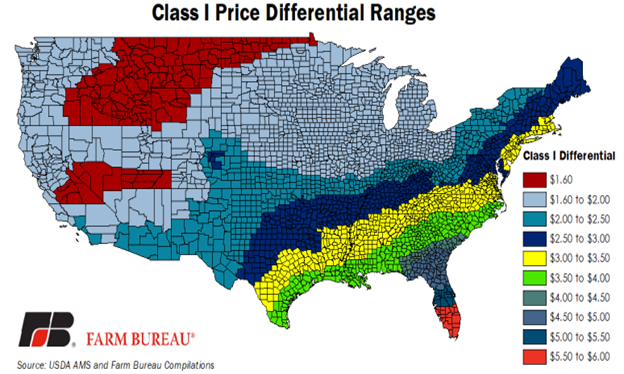

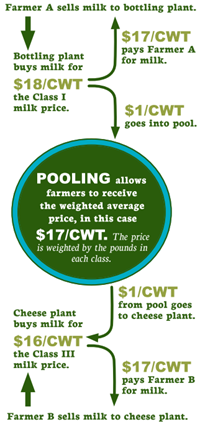

This is a good point in the discussion to introduce the topic of pooling as it has been mentioned several times but has not been discussed in detail. Pooling was created so farmers in the same region would be paid a more uniform price. Instead of some farmers selling to higher value milk classes and others selling to typically lower value milk classes, all the milk in an order is pooled together (economically, not physically) and averaged, so farmers are paid a more uniform price. All Class I processors are required to participate in pooling, and it is voluntary for all other milk class handlers. Under “normal” conditions, a simplistic view of pooling looks something like what is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Simplistic View of Pooling; Sourced from USDA

Producer Payments Out of Pool

To this point, the discussion has focused primarily on handler obligations to the pool. Producer milk value is more straightforward but is also dependent on what kind of milk pricing scheme your FMMO is using.

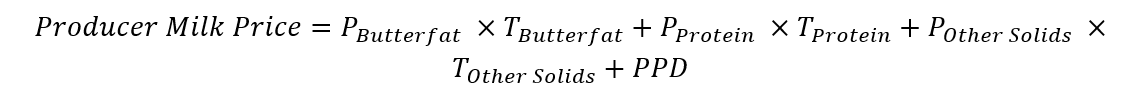

Under MCP, the value of a producer’s milk, or the producer’s payment out of the pool, is given by the equation below. Here T means the milk component test of milk:

Simply put, it is the total value of components in the milk plus the producer price differential (PPD), which can be positive or negative. The component value of the milk is calculated by the price of butterfat multiplied by the producer’s butterfat test, plus the price of protein multiplied by the producer’s protein test, plus the price of other solids multiplied by the producer’s other solids test. Skim-fat is similar to the above equations except the base protein and other solids component levels are always used in place of the component tests.

The PPD exists because the total handler’s obligation to the pool is different from the producer’s payment from the pool. If the handlers pay more into the pool than the total value of payments to producers, then the excess money is divided out across all milk in the pool and added as a positive PPD. Typically differentials in Class I and Class II prices, as well as the fact that the combined value of protein and other solids can be below the value of non-fat solids, makes handlers' obligations to the pool higher than producer payments, also thereby makes the PPD positive. This is not always the case. If total payments to producers are higher than handlers total obligations to the pool, the difference is divided out across all milk and deducted as a negative PPD.

Producer Price Differential

The topic of PPDs came under intense focus over the past few years, due to the large negative PPD’s that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. Handler payments into the pool can be lower than obligations to producers out of the pool for a variety of reasons. Bozic and Wolf (2022) [1] identified 6 factors contributing to lower PPDs.

- Changes in utilization rates. Class I is historically higher value than other classes and contributed to higher handler obligations to the pool. Class I utilization has decreased over time, leading to downward pressure on PPDs.

- Changes in component tests. Specifically, in MCP orders, increases in non-fat solids can decrease PPD because Class I handlers do not have to pay for additional solids.

- Changes in announced dairy prices. Producer’s value for nonfat solids is calculated off the value of protein and other solids used to make whey. However nonfat solids are also used in beverage milk and NFDM. If the value of protein and other solids is higher than the value of NFDM, handler obligations to the pool will be lower than the value of producers’ milk out of the pool.

- Changes in advanced dairy product prices. Class I and II milk prices are announced earlier than Class III and IV. However, these classes all use the same commodities to calculate the price. Therefore, different commodity prices can be used in each price, leading to differences between handler obligations and producer payments.

- Changes in the Class I skim milk pricing equation. Previously the Class I skim milk price was the higher of the Class III and Class IV prices. This was changed to the current equation of the average of these prices plus $0.74/cwt.

- Depooling. Handlers deciding not to pool milk for at least one month. Typically pooling is incentivized by handlers because higher Class I milk prices mean they can pass higher prices onto their producers. However, this was not the case for a period during the pandemic. Depooling caused already low prices to be even lower for some producers.

[1] Bozic M and CA Wolf (2022) “Negative producer price differentials in Federal Milk Marketing Orders: Explanations, implications, and policy options” Journal of Dairy Science 105:424–440. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2021-20664

Want more news on this topic? Farm Bureau members may subscribe for a free email news service, featuring the farm and rural topics that interest them most!